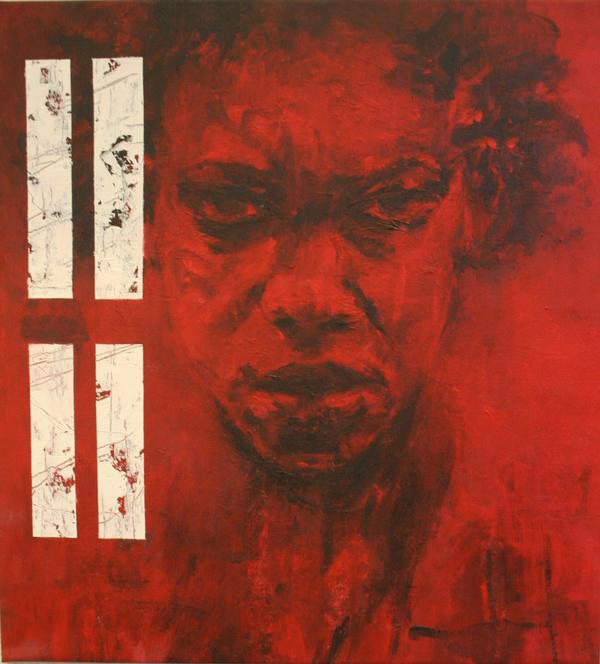

We are pleased to share the digital projection that was shown at the African Burial Ground during the month of December and early January. The artist, Patrick Singh created these works while he was in New York, France and Burkina Faso.

Canary Islands

“If you could sit back and watch clouds and the sky move all night and day, what might you see? This video was shot in the Teide National Park on Tenerife in the Canary Islands of Spain, attached to the northwest coast of Africa. The scenes were captured over the course of the year and include breathtaking views — clouds that seem to flow like water — a setting sun that shows numerous green flashers — the Milky Way Galaxy rising behind towering plants — a colorful double fogbow — lenticular clouds that appear stationary near their mountains peaks — and colorful moon coronas.

David Kagan

inspirational blog

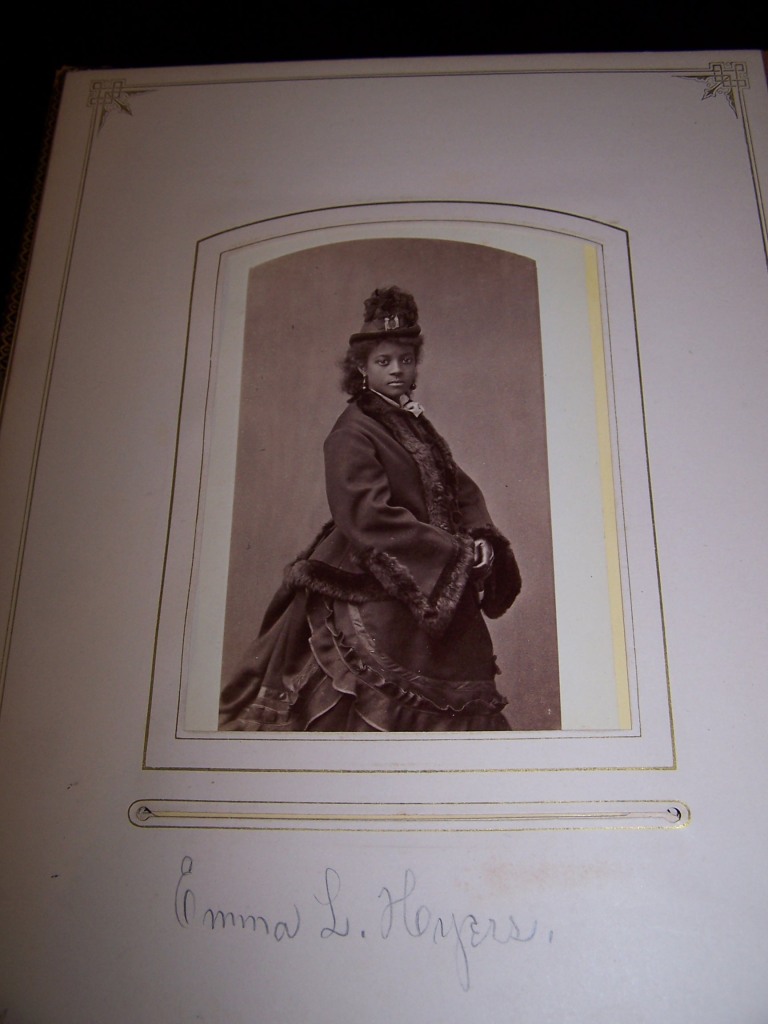

The Hyers Sisters

With Joseph Bradford and Pauline Hopkins, the Hyers Sisters produced the “first full-fledged musical plays… in which African Americans themselves comment on the plight of the slaves and the relief of Emancipation without the disguises of minstrel comedy”, the first of which was Out of Bondage (also known as Out of the Wilderness).

The Hyers Sisters were singers, Anna Madah born in 1855 and Emma Louise born in 1857. Their father, Samuel B. Hyers, came west to Sacramento with their mother, Annie E. Hyers (née Cryer), after the Gold Rush. He made sure his daughters received both piano forte lessons and vocal training with German professor Hugo Sank and later opera singer Josephine D’Ormy and they performed for private parties before making their professional stage debut at on April 22, 1867 at Sacramento’s Metropolitan Theater. Anna was a soprano and Emma a contralto. Under their father’s management, they embarked on their first transcontinental tour in 1871. On August 12, 1871, they performed in Salt Lake City to much acclaim.

They were later called “a rare musical treat” by St. Joseph Missouri’s Daily Herald and earned equal praise in Chicago, Cleveland, and New York City. Their tour reached Worcester and Springfield, Massachusetts, as well as New Haven, Providence. They visited Boston, which was known to be extremely critical of new acts, and were also well-received, performing in the 1872 World Peace Jubilee which was one of, if not, the first integrated major musical production in the country.

The Hyers’ family organized a theater company, where they produced musical dramas starring Anna and Emma, including “Out of Bondage,” written by Joseph Bradford and premiered in 1876, “Urlina, the African Princess” by Getchell written by E. S. Getchell and premiered in 1879, “The Underground Railway,” by Pauline Hopkins in July 1880, and Hopkin’s stage version of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in March 1880. In addition, there was “Colored Aristocracy” by Hopkins. Overall, they had at least six shows between the late 1870s and 1880s. They set the path for black musical theater and performance in the years that followed. They traveled until the mid-1880s with their own shows and continued to appear on stage into the 1890s. Though Emma Louise had died, in 1901, Anna Madah continued to travel with a show of John Isham.

Celebrating Black History Anew

As we begin to celebrate Black History Month, how many of us know its beginnings. And how many of us shape our lives in the manner of its founder Carter G. Woodson. Today, we live in a global world that requires us to be more competitive and to showcase our talents. Those of African decent have often been forced to meet that challenge with unnecessary obstacles but if we look to those who had the faith, we can meet this new world with our heads held high. So, let’s just do it.

The story of Black History Month begins in Chicago during the late summer of 1915. An alumnus of the University of Chicago with many friends in the city, Carter G. Woodson traveled from Washington, D.C. to participate in a national celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of emancipation sponsored by the state of Illinois.

Thousands of African Americans traveled from across the country to see exhibits highlighting the progress their people had made since the destruction of slavery. Awarded a doctorate in Harvard three years earlier, Woodson joined the other exhibitors with a black history display.

Despite being held at the Coliseum, the site of the 1912 Republican convention, an overflow crowd of six to twelve thousand waited outside for their turn to view the exhibits. Inspired by the three-week

celebration, Woodson decided to form an organization to promote the scientific study of black life and history before leaving town. On September 9th, Woodson met at the Wabash YMCA with AL Jackson and three others and formed the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH).

He hoped that others would popularize the findings that he and other black intellectuals would publish in The Journal of Negro History, which he established in 1916. As early as 1920, Woodson urged black civic organizations to promote the achievements that researchers were uncovering. A graduate member of Omega Psi Phi, he urged his fraternity brothers to take up the work. In 1924, they responded with the creation of Negro History and Literature Week, which they renamed Negro History Achievement Week. Their outreach was significant, but Woodson desired greater impact. As he told an audience of Hampton Institute students, “We are going back to that beautiful history and it is going To inspire us to greater achievements.”

In 1925, he decided that the Association had to shoulder the responsibility. Going forward it would both create and popularize knowledge about the black past. He sent out a press release announcing Negro History Week in February, 1926.

Woodson chose February for reasons of tradition and reform. It is commonly said that Woodson selected February to encompass the birthdays of two great Americans who played a prominent role in shaping black history, namely Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, whose birthdays are the 12th and the 14th, respectively. More importantly, he chose them for reasons of tradition. Since Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, the black community, along with other Republicans, had been celebrating the fallen President’s birthday. And since the late 1890s, black communities across the country had been celebrating Douglass’. Well aware of the pre-existing celebrations, Woodson built Negro History Week around traditional days of commemorating the black past. He was asking the public to extend their study of black history, not to create a new tradition. In doing so, he increased his chances for success.

Yet Woodson was up to something more than building on tradition. Without saying so, he aimed to reform it from the study of two great men to a great race. Though he admired both men, Woodson had never been fond of the celebrations held in their honor. He railed against the “ignorant spellbinders” who addressed large, convivial gatherings and displayed their lack of knowledge about the men and their contributions to history. More importantly, Woodson believed that history was made by the people, not simply or primarily by great men. He envisioned the study and celebration of the Negro as a race, not simply as the producers of a great man. And Lincoln, however great, had not freed the slaves—the Union Army, including hundreds of thousands of black soldiers and sailors, had done that. Rather than focusing on two men, the black community, he believed, should focus on the countless black men and women who had contributed to the advance of human civilization.

From the beginning, Woodson was overwhelmed by the response to his call. Negro History Week appeared across the country in schools and before the public. The 1920s was the decade of the New

Negro, a name given to the Post-War I generation because of its rising racial pride and consciousness. Urbanization and industrialization had brought over a million African Americans from the rural South into big cities of the nation. The expanding black middle class became participants in and consumers of black literature and culture. Black history clubs sprang up, teachers demanded materials to instruct their pupils, and progressive whites stepped and endorsed the efforts.

Woodson and the Association scrambled to meet the demand. They set a theme for the annual celebration, and provided study materials—pictures, lessons for teachers, plays for historical performances, and posters of important dates and people. Provisioned with a steady flow of knowledge, high schools in progressive communities formed Negro History Clubs. To serve the desire of history buffs to participate in the re-education of black folks and the nation, ASNLH formed branches that stretched from coast to coast. In 1937, at the urging of Mary McLeod Bethune, Woodson established the Negro History Bulletin, which focused on the annual theme. As black populations grew,mayors issued Negro History Week proclamations, and in cities like Syracuse progressive whites joined Negro History Week with National Brotherhood Week.

Like most ideas that resonate with the spirit of the times, Negro History Week proved to be more dynamic than Woodson or the Association could control. By the 1930s, Woodson complained about

the intellectual charlatans, black and white, popping up everywhere seeking to take advantage of the public interest in black history. He warned teachers not to invite speakers who had less knowledge than the students themselves. Increasingly publishing houses that had previously ignored black topics and authors rushed to put books on the market and in the schools. Instant experts appeared everywhere, and non-scholarly works appeared from “mushroom presses.” In America, nothing popular escapes either commercialization or eventual trivialization, and so Woodson, the constant reformer, had his hands full in promoting celebrations worthy of the people who had made the history.

Well before his death in 1950, Woodson believed that the weekly celebrations—not the study or celebration of black history–would eventually come to an end. In fact, Woodson never viewed black

history as a one-week affair. He pressed for schools to use Negro History Week to demonstrate what students learned all year. In the same vein, he established a black studies extension program to reach adults throughout the year. It was in this sense that blacks would learn of their past on a daily basis that he looked forward to the time when an annual celebration would no longer be necessary. Generations before Morgan Freeman and other advocates of all-year commemorations, Woodson believed that black history was too important to America and the world to be crammed into a limited time frame. He spoke of a shift from Negro History Week to Negro History Year.

In the 1940s, efforts began slowly within the black community to expand the study of black history in the schools and black history celebrations before the public. In the South, black teachers often taught Negro History as a supplement to United States history. One early beneficiary of the movement reported that his teacher would hide Woodson’s textbook beneath his desk to avoid drawing the wrath of the principal. During the Civil Rights Movement in the South, the Freedom Schools incorporated black history into the curriculum to advance social change. The Negro History movement was an intellectual insurgency that was part of every larger effort to transform race

relations.

The 1960s had a dramatic effect on the study and celebration of black history. Before the decade was over, Negro History Week would be well on its way to becoming Black History Month. The shift to a month-long celebration began even before Dr. Woodson death. As early as 1940s, blacks in West Virginia, a state where Woodson often spoke, began to celebrate February as Negro History Month. In Chicago, a now forgotten cultural activist, Fredrick H. Hammaurabi, started celebrating Negro History Month in the mid-1960s. Having taken an African name in the 1930s, Hammaurabi used his cultural center, the House of Knowledge, to fuse African consciousness with the study of the black past. By the late 1960s, as young blacks on college campuses became increasingly conscious of links with Africa, Black History Month replaced Negro History Week at a quickening pace. Within the Association, younger intellectuals, part of the awakening, prodded Woodson’s organization to change with the times. They succeeded. In 1976, fifty years after the first celebration, the Association used its influence to institutionalize the shifts from a week to a month and from Negro history to black history. Since the mid-1970s, every American president, Democrat and Republican, has issued proclamations endorsing the Association’s annual theme.

What Carter G. Woodson would say about the continued celebrations is unknown, but he would smile on all honest efforts to make black history a field of serious study and provide the public with thoughtful celebrations.

Daryl Michael Scott

dms@darylmichaelscott.com

Professor of History

Howard University

Vice President of Program, ASALH

© 2011, 2010, 2009 ASALH

ASALH at http://www.asalh.org

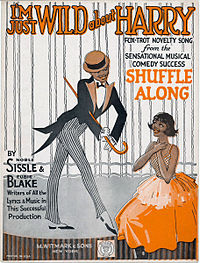

Noble Sissle

>

Noble Sissle was an American jazz lyricist, composer, singer, playwright and band leader. Above is Sissle’s 1928 version of Westward Bound.

Sissle was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on July 10, 1889. his parents were very religious but loved music. He joined the 369th Regimental Band led by the great James Reese Europe. During this time, he also met Eubie Blake who he collaborated with for years after the death of Europe.

Noble Sissle was one of African-American music’s unsung tradition-builders. As half of the duo that composed Shuffle Along, he helped to bring African-American creativity to a new level on the Broadway stage. As a bandleader, Sissle nurtured the careers of vocalist Lena Horne and other important musicians, and he participated fundamentally in the popularization of African-American jazz and pop in Europe. Sissle went on to compose memorable jazz tunes like I’m Just Wild About Harry and Shuffle Along. His song Viper Mad was in Woody Allen’s film Sweet and Lowdown.

Photojournalist Bill Hudson

This week Flavorwire listed the ten most essential Civil Rights photographers. As we looked at the photos, We wanted to focus on Bill Hudson, an Associated Press photographer at that time. His images reminds us of the Arab Spring that shocked the world in 2011. Freedom doesn’t come without struggle. As we begin this new year, it is our hope that we can move from protest to real action that would lead to real hope.

The Story Behind the Photo:

On July 15, 1963, photographer Bill Hudson snapped this photograph as members of the Birmingham Fire Department turned their hoses full force on civil rights demonstrators. It wasn’t the first time that Hudson and other photographers and cameramen of the era captured such striking images that stirred the nation’s moral consciousness and inspired national and international support for the black struggle for equal rights. In an interview years later, Hudson said that his only priorities were “making pictures and staying alive” and not getting hit by one of those high-pressure water hoses or bit by a dog.

In the spring of 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Coalition led a strategic campaign in Birmingham, Alabama that was aimed at ending the city’s segregation policies and practices. Through sit-ins, kneel-ins, boycotts, marches, and mass meetings, demonstrators also hoped to pressure business leader s to open retail jobs and employment to people of all races. By intentionally provoking arrest through non-violent direct action, King believed that if they could “crack Birmingham” then they could “crack the South” and dismantle Jim Crow.

Birmingham’s Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, a staunch segregationist, promised bloodshed if demonstrators continued to defy the law. When the city’s jails became crowded with thousands of demonstrators and there weren’t enough squad cars to make arrests, Conner, whose authority extended to the fire department, ordered hoses to be turned on demonstrators.

To Connor’s surprise, and to the dismay of the Kennedy administration and some black civil rights leaders, King and local leaders of the SCLC, in a controversial move, recruited children as young as eight years old to participate in demonstrations. They were taught how to protect their heads, huddle together on the ground when hit with water jet, and how to be arrested. Hudson and other cameramen captured images of young demonstrators clutching poles, being sprayed against store windows, and women being lifted over the tops of cars. They took shots of young boys’ shirts being ripped off and their bodies being rolled down the streets water pressure set at a level that was strong enough to peel bark off trees and separate brick from mortar.

In the backgrounds of these images, onlookers can sometimes be seen taunting police officers and firefighters, and tossing broken concrete, rocks and bottles in a futile effort to stop the abuse by authorities. And other times, as in the case of the photo captured above, blacks can be seen behind the strong white mist with their hands on their hips, shoulders dropped, and hands by their side, helpless and perhaps contemplating the irony that the very people who were supposed to protect the public had become villains.

Westward Bound interview with our artist Patrick Singh

The West Harlem Art Fund is so pleased to be working with Patrick Singh again. This Skyped interview was done while the artist was in the South of France with his gallerist. His bio is below in English and French.

Born to an Indian father and a French mother, Patrick was predestined to multicultural encounters. He spent his childhood traveling between the South of France and London, England. He is a holder of a State Diploma in Managing Leisure and Cultural Activities – French “Diplome d’Etat Relatif aux Fonctions d’Animation”.

Since 1997, Singh’s career has been punctuated by international exhibitions – collective and individual – along with artistic residencies throughout Europe, South America and Asia. Singh’s work is exhibited in multiple collections, including the Anne Cros Gallery located in the South of France. His visions come to life under his brush without his using models.

Né à un père indien et à une mère française, Patrick a été prédestiné aux rencontres multiculturelles. Il a passé son enfance voyageant entre le Sud de la France et Londres, Angleterre. Il est un détenteur d’un Diplôme d’État dans le Loisir se Débrouillant et les Activités Culturelles – le français “Diplome d’Etat Relatif aux Fonctions d’Animation”.

Depuis 1997, la carrière de Singh a été ponctuée par les expositions internationales – collectif et individuel – avec les résidences artistiques partout dans l’Europe, l’Amérique du Sud et l’Asie. Le travail de Singh est exposé dans les collections multiples, en incluant la Galerie d’Anne Cros trouvée au Sud de la France. Ses visions reprennent conscience sous sa brosse avec de ses modèles d’utilisation.

The Real History of Kwanzaa

Many believe that Maulana Karenga, professor of Africana Studies, scholar/activist and author is the creator of Kwanzaa. Mr. Karenga was able to codify the holiday with African references and influences but the spirit of the holiday originated with Julius Kambarage Nyerere. Though he was a suspicious of capitalism, his aim politically and culturally was to improve his country and all of Africa.

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian politician who served as the first President of Tanzania and previously Tanganyika, from the country’s founding in 1961 until his retirement in 1985.

Born in Tanganyika to Nyerere Burito (1860–1942), Chief of the Zanaki, Nyerere was known by the Swahili name Mwalimu or ‘teacher’, his profession prior to politics. He was also referred to as Baba wa Taifa (Father of the Nation). Nyerere received his higher education at Makerere University in Kampala and the University of Edinburgh. After he returned to Tanganyika, he worked as a teacher. In 1954, he helped form the Tanganyika African National Union.

In 1961, Nyerere was elected Tanganyika’s first Prime

Minister, and following independence, in 1962, the country’s first President. In 1964, Tanganyika became politically united with Zanzibar and was renamed to Tanzania. In 1965, a one-party election returned Nyerere to power. Two years later, he issued the Arusha Declaration, which outlined his socialist vision of ujamaa that came to dominate his policies.

Nyerere retired in 1985, while remaining the chairman of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi. He died of leukemia in London in 1999. In 2009, Nyerere was named “World Hero of Social Justice” by the president of the United Nations General Assembly.

Cultural Influence

Nyerere continued to influence the people of Tanzania in the years following his presidency. His broader ideas of socialism live on in the rap and hip hop artists of Tanzania. Nyerere believed socialism was an attitude of mind that barred discrimination and entailed equality of all human beings. Therefore, ujamaa can be said to have created the social environment for the development of hip hop culture. Like in other countries, hip hop emerged in post-colonial Tanzania when divisions among the population were prominent, whether by class, ethnicity or gender. Rappers’ broadcast messages of freedom, unity, and family, topics that are all reminiscent of the spirit Nyerere put forth in ujamaa. In addition, Nyerere supported the presence of foreign cultures in Tanzania saying, “a nation which refuses to learn from foreign cultures is nothing but a nation of idiots and lunatics…[but] to learn from other cultures does not mean we should abandon our own.” Under his leadership, the Ministry of National Culture and Youth was created in order to allow Tanzanian popular culture, in this case hip hop, to develop and flower. As a result of Nyerere’s presence in Tanzania, the genre of hip hop was welcomed from overseas in Tanzania and melded with the spirit of ujamaa.

To learn more about the Arusha Declaration, go to the Wikipedia link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arusha_Declaration

Video Commentaries on artist Patrick Singh — Part Two

More Skyped interviews that were created by Savona Bailey-McClain, Executive Director & Chief Curator of the West Harlem Art Fund, Inc. and National Park Service, Manhattan Sites. The commentaries were recorded while the participants were in Miami, Florida and Oakland, California. Again, the participants gave very thoughtful views of the artist’s work and its relationship to the African Burial Ground or African artistic expressions.

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976) is a photo conceptual artist working primarily with themes related to identity, history and popular culture. Thomas’s process often involves editing existing photographs and presenting them in a new format. His work often examines the commoditization of Black identity in advertising and popular culture and urges the viewer to think critically about representations in media and beyond. Willis Thomas received his BFA from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and his MFA in photography, along with an MA in visual criticism, from California College of the Arts (CCA) in San Francisco. His work is in numerous public collections including The Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, The High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the Museum of Fine Art in Houston. His collaborative projects have been installed publicly in California, and featured at the Sundance Film Festival. Thomas is currently a fellow at the W.E.B. DuBois Institute at Harvard University; and he is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City.

Chris Johnson (American, born 1948) is a photographic and video artist, writer, curator and arts administrator. Johnson studied photography with Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Wynn Bullock; and his artwork has been exhibited at the Oakland Museum of California and at the Mills College Museum. In 1994 he co-produced a large performance work in Oakland titled “The Roof is on Fire” bringing together inner-city high school students and adults. In 1996 he produced an innovative one-hour video piece titled “Question Bridge” that investigates class divisions within the black community. In 1999 Oakland Mayor Jerry Brown appointed Johnson to be Chair of the Oakland Cultural Affairs Commission to advise on all matters affecting cultural development in Oakland. Johnson is currently a tenured Full Professor of Photography at the California College of the Arts.

Video Commentaries on artist Patrick Singh — Part One

These Skyped interviews were created by Savona Bailey-McClain, Executive Director & Chief Curator of the West Harlem Art Fund, Inc. and National Park Service, Manhattan Sites. The commentaries were recorded while the participants were in Berlin, Atlanta and Harlem. All of the participants gave very thoughtful views of the artist’s work and its relationship to the African Burial Ground or African artistic expressions.

Kamal Sinclair (American, born 1976) is a professional artist, teaching artist, and producer of live and transmedia art. Kamal obtained her BFA from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and graduated with honors from Georgia State University’s Robinson College of Business MBA program. Her professional career began as a cast member of STOMP where she performed in the national and international tours, as well as on the Emmy Awards, MTV’s Beach House, Good Morning America, The Today Show, BET, and PBS’s Reading Rainbow. Sinclair was the founding artistic director of Universal Arts and creative director for many festivals and awards shows. She taught business courses to artists through the Savannah School of Art and Design (SCAD) and Fractured U: Continuing Education for the DIY Artist. Sinclair is also a periodic contributor to the acclaimed theatre publication, Black Masks.

Birta Guðjónsdóttir (Born 1977) is an artist and curator. She obtained her MFA degree of Fine Arts from the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam and a BFA-degree from The Icelandic Academy of the Arts. In 2009-´11 she was a director of The Living Art Museum in Reykjavik. In 2008-´09 she was an artistic director and chief curator at exhibition space 101 Projects, Reykjavik. In 2005-´08 she had the position of chief curator of SAFN Art Collection, Reykjavik. In 2008 she worked as curator´s assistant at MuHKA; Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp. In 2007-08 she took part in the Nordic Baltic Curatorial Platform project, initiated by FRAME; Finnish Fund for Art Exchange. In 2011 she participated in the Curatorial Intensive at ICI-New York and The Cornwall Workshop organized by Tate St. Ives Museum in S-England. She has curated shows in Melbourne, New York, St Petersburg, Copenhagen and most major art museums in Reykjavik, and been an editor of four exhibition catalogues. She has been on advisory boards of the Icelandic Art Center, The Icelandic Academy of the Arts and for various commissions and art prizes. She has produced her home-gallery Dwarf Gallery since 2002, is a founding board member of Sequences Art Festival, a member of IKT, International Association of Curators of Contemporary Art and a member of curator’s collective WAG. As an artist, she has participated in over 30 solo- and group exhibitions.

Dianne Smith (born 1965) is an abstract painter, sculptor, and installation artist. Her work has beenexhibited in solo and group exhibitions in New York City’s Soho and Chelsea artdistricts as well as, numerous galleries and institutions throughout the UnitedStates. She is an educator in the field of Aesthetic Education at LincolnCenter Institute, which is a part of New York City’s Lincoln Center For the Performing Arts. Since the invitation to join the Institute over five years ago she has taught k-12 in public schools throughout the Tri-State area. Her work as a teaching artist also extends to under graduate and graduate courses in various colleges and universities such as: Lehman College, Columbia University Teachers College, City College, and St. John’s University to name a few.Recently she was invited to join the team at The Center For arts Education in New York City. In 2007, Dianne was one of the artists featured in the Boondoggle Film Documentary Colored Frames. The film took a look back at fifty years in African-American Art, and also featured other artists such as Benny Andrews, Ed Clark and Danny Simmons.That same year the historical Abyssinian Baptist Church, which is New York’s oldest African American church commissioned Smith to create the artwork commemorating their 2008 Bicentennial. In addition, she co-produced an online radio show the New Palette, for ArtonAir.org (Art International Radio)dedicated to visual artists of color. In1995, she presented Poet Dr. Maya Angelou and Broadway Choreographer George Faison each with one of her paintings: Spirit of My Ancestors I and II. Her work is also in the private collections of Danny Simmons, Vivica A. Fox, Rev. and Mrs. Calvin O. Butts,III, Cicely Tyson, Arthur Mitchell and Terry McMillian. Dianne is a Bronx native of Belizean descent. She attended LaGuardia High School of Music and Art, the Otis Parsons School of Design and the Fashion Institute of Technology. Smith is currently pursuing her MFA at Transart Institute in Berlin. She currently lives and works in Harlem.